Montreal’s festival season is in full swing, reaching a midsummer peak with the First Peoples’ Festival from July 29 to August 6, when it bridges the end of Just for Laughs and Osheaga (which finally announced a formal ban on Native feather headdresses!).

Over its eight days, the FPF straddles the line between a conference and a party, boasting musical acts like Kashtin legend Florent Vollant (performing with folksinger and environmental activist Richard Desjardins), art shows at various locations, seminars such as “Indigenous Media and Arts: from Apartheid to Hypervisibility” – and of course, a whole lot of movies.

Here are a few of this year’s film and video highlights:

The Wolverine: The Fight of the James Bay Cree

Ernest Webb (Eeyou Istchee, 9 min)

This short film from Rezolution Pictures, by Nation co-founder Ernest Webb, will be a focal point at the festival. Last year, speaking to the Bureau des Audiences Publiques sur l’Environment (BAPE) hearings about the proposed Matoush uranium extraction project near Mistissini, Eastmain’s Jamie Moses made a surprising statement. Instead of discussing the issue of uranium, or even raising any ecological threat, he simply spoke about his connection to the land – and then he told the story of the Wolverine and the Giant Skunk, a well-known Cree legend.

This short film from Rezolution Pictures, by Nation co-founder Ernest Webb, will be a focal point at the festival. Last year, speaking to the Bureau des Audiences Publiques sur l’Environment (BAPE) hearings about the proposed Matoush uranium extraction project near Mistissini, Eastmain’s Jamie Moses made a surprising statement. Instead of discussing the issue of uranium, or even raising any ecological threat, he simply spoke about his connection to the land – and then he told the story of the Wolverine and the Giant Skunk, a well-known Cree legend.

It was a breathtaking moment before the commission, one that turned the entire discussion about uranium and mining on its head and placed the focus where it belonged: on the land, the people and their history.

Webb was obviously paying close attention, as he’s woven a recording of that statement into the narrative of this film. You’ll hear Moses retelling the legend over scenes on the land, re-enactment of the events of the story, and artist Amanda T. Sam’s visionary drawings of the legend. (Sam’s drawings are breathtaking to begin with, but grow twice as amazing on learning that she did them with a broken hand.)

Antigone

Matt Keay (Canada, 44 min)

Though the idea of tragedy in the modern world comes to us from ancient Greece, Woodland Cree playwright Deanne Kasokeo believed it could be used to channel the pain of modern life on the rez. With that in mind, she adapted the Greek tragedy Antigone by Sophocles (dating back to 441 BC) to handle issues of modern life in post-colonial Canada.

Though the idea of tragedy in the modern world comes to us from ancient Greece, Woodland Cree playwright Deanne Kasokeo believed it could be used to channel the pain of modern life on the rez. With that in mind, she adapted the Greek tragedy Antigone by Sophocles (dating back to 441 BC) to handle issues of modern life in post-colonial Canada.

The original play deals with ideas of loyalty and betrayal, following a sister trying to bury her brother who died a traitor, and – in true tragic fashion – ends in multiple suicides. Adapting it for modern Saskatchewan, Kasokeo spared no attacks on the racism of colonial Canadians or on the corruption of Indigenous leaders, whom she sees as tools of the colonial state. While the adapted version of the play was wildly popular on its release in Regina in 1998, in 2011 the play was banned outright from the Poundmaker First Nation, 200 km north of Saskatoon.

Matt Keay’s documentary explores Kasokeo’s adaptation and the trouble it caused in the Poundmaker community, interviewing Kasokeo and the actors involved in the play, and placing it in the context of ongoing Indigenous issues both on reserve and across Canada.

Yvy Maraey: Land without Evil (Yvy Maraey: tierra sin mal)

Juan Carlos Valdivia (Bolivia, 105 min)

Bolivian director Juan Carlos Valdivia’s Yvy Maraey is a portrait of the clash of ideas that take place in the collision between Indigenous and settler cultures. Valdiva portrays Andres, a character very much like himself – a white film director who wishes to make a movie about the Indigenous Guarani peoples. He hires Guarani guide Yari (Elio Ortez) to introduce him to the culture and its people as they follow path of a Swedish filmmaker who filmed the Guarani over a century ago.

Bolivian director Juan Carlos Valdivia’s Yvy Maraey is a portrait of the clash of ideas that take place in the collision between Indigenous and settler cultures. Valdiva portrays Andres, a character very much like himself – a white film director who wishes to make a movie about the Indigenous Guarani peoples. He hires Guarani guide Yari (Elio Ortez) to introduce him to the culture and its people as they follow path of a Swedish filmmaker who filmed the Guarani over a century ago.

During a journey through breathtaking mountain landscapes, Andres and Yari argue about issues of power, origins, identity and the desires of white people in a Native land. Andres is interested in the abstract: he wants to explore the Guarani legend of a “land without evil,” which he is intent to locate. Yari, meanwhile, is focused on the present day: he fights to convince Andres that his concerns should be focused on preserving land and saving the Indigenous people who inhabit it, rather than on legends and ideas.

Yvy Maraey is a film of big (and sometimes pretentious) ideas and big images, stretching philosophical discussion across amazing shots of the enormous land of southeastern Bolivia.

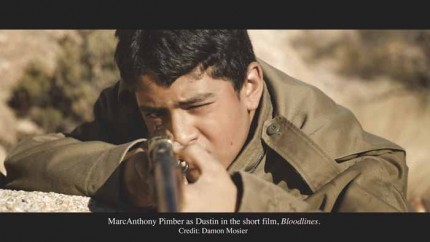

Bloodlines

Christopher Nataanii Cegielski (Navajo Nation, 11 min)

A wolf has been killing the livestock and the family that lives on the ranch – two young brothers and their dour, abusive father – are at their breaking point in this short film by Arizona Navajo filmmaker Christopher Nataanii Cegielski. When their father fails to shoot the wolf, the boys steal his rifle while he’s sleeping to hunt it down.

A wolf has been killing the livestock and the family that lives on the ranch – two young brothers and their dour, abusive father – are at their breaking point in this short film by Arizona Navajo filmmaker Christopher Nataanii Cegielski. When their father fails to shoot the wolf, the boys steal his rifle while he’s sleeping to hunt it down.

Bloodlines is an impressively quiet film: there are only three words in its 11 minutes. Instead, Cegielski encourages the viewer to think about the relationship between the people and the land, a hilly desert full of giant boulders. Like the wolf that is terrorizing their ranch, the landscape is both threatening and beautiful. For the two boys out hunting the wolf, the story comes down to deciding when something is too beautiful to die, or too threatening to live. The film was produced as Cegielski’s senior thesis for his Bachelor of Fine Arts in film and has been touring festivals since last year.

Legend of the Storm

Roxann Whitebean (Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, 16 min)

Kahnawake director Roxann Whitebean’s dreamlike short film is “Dedicated to the Children of War,” and begins with a specific reference to the Kanesatake/Oka Crisis in 1990. Strung together by a narrator who’s simultaneously recounting events and telling the viewer something about them, the film follows a mother and her children who allegorically represent the experiences of those inside the besieged communities of Kahnawake and Kanesetake. Over a series of set-piece scenes, Whitebean explores emotions of threat and suffering mainly from the perspective of a pre-teen girl witnessing and experiencing violence while also attempting to maintain an atmosphere of normality at home.

Le Chemin Rouge

Thérèse Ottawa (Atikamekw Nation of Opitciwan, 15 min)

If you speak French, it’s worth checking out Atikamekw director Thérèse Ottawa’s moving documentary Le Chemin Rouge. The understated short film follows 21-year-old Tony Chachai, a powwow dancer from the Atikamekw community of Opitciwan who has found refuge from addiction in the culture and community of powwows. At the age of 18, a heavy drug and alcohol user, Tony was brought to a powwow by a friend and recognized immediately a culture to which he could belong and contribute. On the eve of becoming a father himself, Tony reflects on his mother, her addictions, and the impact her suffering had on his life, but also his ability to make things different for the next generation. The film is a testament to the power of powwow culture to bring suffering individuals back from the brink of self-destruction.

Sumé: The Sound of a Revolution (Sumé: mumisitsinerup nipaa)

Inuk Silis Høegh (Greenland, 73 min)

The release last fall of the remarkably popular Native North America Vol. 1 compilation, bringing together Indigenous rock and country songs from the 1960s through the 1980s, was a critical success. Unheard for decades, suddenly songs by Eastmain’s Lloyd Cheechoo and Mistissini’s Morley Loon and Willie Mitchell were filling the airwaves and crossing the internet, alongside contemporaries like Alberta’s Chieftones and Puvirnituq’s Sikumiut. The collection was a reminder that even when music is forgotten, it doesn’t lose its power to touch listeners – all it needs is ears.

At the same time Cheechoo and Loon and Mitchell were recording in and around Eeyou Istchee, Sumé was making records further east in Greenland. The first band to sing rock and roll and record in Greenlandic at a time when Greenland had few powers under its Danish rule, Sumé represented a spirit of rebellion against colonialism. This was made clear by the jacket of their first record, which showed an Inuit standing triumphant over a European corpse riddled with arrows.

The film reels through the archives to explore the history of the band, begun by four Greenlanders who met while students in Denmark. Marking the political zeitgeist of early 1970s Denmark, Sumé released albums to Greenlandic and Danish acclaim for four brief years before calling it quits in 1977 – shortly before the establishment of a Home Rule government in Greenland. That win, in 1979, granted Greenlanders a certain degree of internal government, and many credited Sumé for helping build the culture of Greenlandic pride and ambition that led to its creation.