Jimmy Cooper is beginning to wonder the meaning of being

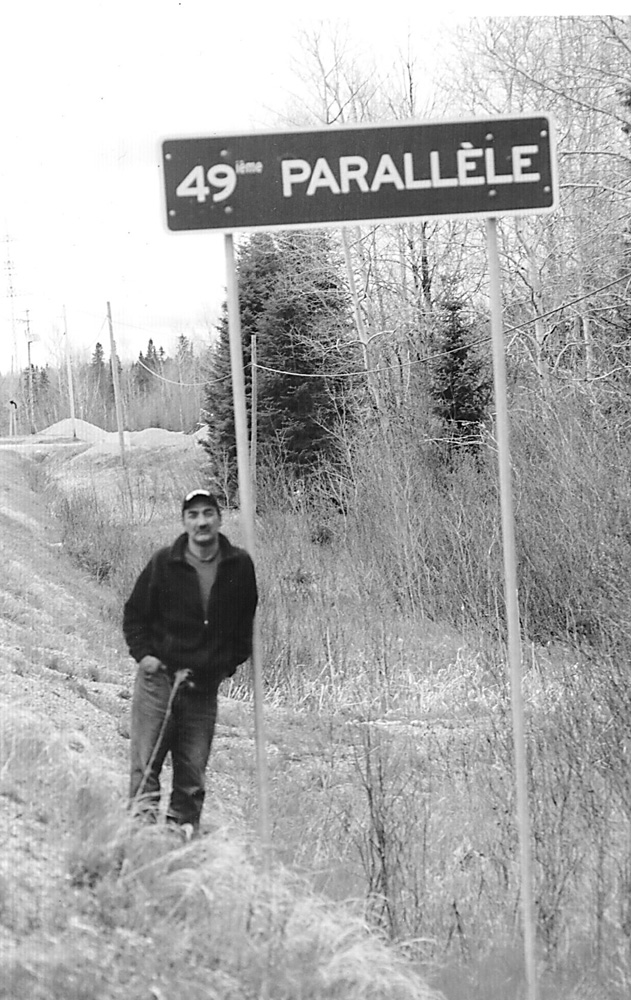

Cree in today’s world after a Val d’Or Court ruling found him guilty of hunting south of the 49th parallel – even though he had signed an agreement with the farmer who owned the land he was hunting on.

Having grown up in the bush, Cooper says he has always hunted and lived the way a traditional Cree would. Until the day he was caught hunting in a “grey” area.

Under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, the hunting territory is cut into three categories. The Northern area, Southern area, and something called a Buffer Zone. The incident occurred in the Buffer Zone.

But it’s what followed that has mystified Cooper even further. He is disappointed with the reaction of the Grand Council of the Crees, which they would pay his fines – but only if he agreed to plead guilty. “It seems to me that the Grand Council has a policy of not going to court with Quebec since the Paix des Braves Agreement was signed,” Cooper said.

The problem is that the territory in question has not been clearly defined as to who can hunt and fish there. It’s a problem that was supposed to be rectified shortly after the JBNQA was signed, but is still in question.

“The Grand Council never told me about the definitions of where I could hunt as a Cree,” Cooper fumed. “I think they could have handled my situation better. Why wasn’t this issue put into one of their supplementary agreements a long time ago?”

Until very recently, he had to fight for his hunting rights without the help of the Grand Council. A letter written to the GCC and the Waswanipi Band Council, the lawyers representing the Grand Council make reference to their specific instructions from the GCC. The letter, signed August 19, 2004, by David Kalmakoff of the law firm of Hutchins, Grant and Associates, reads in part:

“…to continue to act on Mr. Cooper’s behalf in this matter on the condition that Mr. Cooper would decide to render a plea of guilty and that counsel would seek a discharge so that Mr. Cooper might not have a criminal record in relation to this defense.

“I spoke to Mr. Cooper today and explained the situation to him. He informed me that having considered his position carefully he remains unwilling to plead guilty to the charge he faces and insists on raising his Aboriginal rights as a defense.

“I explained to him that as a result of the conflict between our mandate from the Cree Nation of Waswanipi and his instructions to us in this regard we, and Ms. Flavia Longo, would be withdrawing from acting as council for him and that unless he made other arrangements for himself he would be unrepresented in this matter. Mr. Cooper understood and plans to appear in court on Monday acting on his own behalf. ”

“The deal was that I would plead guilty and they would pay for my lawyer and whatever expenses required for that case,” said Cooper. “But I wanted to plead not guilty because why would I be guilty while practicing my traditional pursuits?”

According to Waswanipi Chief Robert Kitchen, however, the Grand Council has changed its position and is expected to discuss the issue in their Council Board meeting later this month.

Kitchen told the Nation that the Grand Council wants to use this as a test case and that it’ll probably take years before a decision is rendered.

“There were previous cases where Crees fished in that area, but they paid the fine and that was it. With Jimmy’s case, it’ll take quite a bit of time and money to prove that we have rights to hunt and fish in that area and to settle our claims to that land,” he said.

The issue is a very contentious one, and that may have been why the Grand Council did not want to tackle it head on.

“The Buffer Zone as well as other areas are in question right now,” said Kitchen. “They are claimed by us as well as other nations like the Algonquins. We’re hoping to define and come to an agreement with Quebec and the other nations on the land rights issue in the next few years so we’ll know who is entitled to hunt in these areas.” Cooper said that there seems to be a double standard in regards to hunting in the province and he wants to get to the bottom of it. “If the white people can come up here and hunt in our territory, why can’t we go down there and hunt as well?”

He also added that he will not be intimidated and let game wardens dictate his Cree rights. He will go goose hunting in the spring and hopes other Waswanipi residents who have been scared to hunt in that area since his case came to light will follow.

A few years back, Cooper started hunting outside of his usual grounds, “following the game” as he called it.

“Who goes hunting where there’s no game?” he asked. “A hunter knows what he’s doing, so I move where I need to, following the migratory birds.”

His generosity drove him to hunt a little extra, in order to give meat to elders and widows.

One of the newer areas included Vassan, near Amos. He never had any trouble using a farmer’s field to hunt until that day on April 26th, 2002.

“I had made an agreement [Autorisation de Chasse et Pêche] with the farmer that I was going to use his field to hunt,” Cooper recounted. “My son and I went out into his field and got into our boat. We didn’t have a blind, just camouflage gear. We had shot six geese by noon and that’s when the fun started.”

According to Cooper, there were other Crees who came by and had started to shoot at the geese not far from the highway. He later found out that a game warden was on his way to work, saw the Crees, took down Cooper’s license plate number and alerted his colleagues.

“Later in the day, a game warden came and asked me where I was from,” said Cooper. “I told him. Then they said, ‘You’re not supposed to be here, you’re a Cree and you’re not allowed to be beyond the 49th parallel.’ I showed them the agreement I had with the farmer, so they called the FQF (Fédération Québécois de la Faune) and told me that this agreement is not good.”

With that, they told him to pack up and go home.

“There were six game wardens,” he observed. “I said, I’m only going to leave the property if you promise me you won’t seize anything.’ They had a video camera and they videotaped everything, my guns, geese, boats and my car.

“They didn’t say anything about charges at the time,” added an incensed Cooper. “It was only once I received the papers on January 3rd, 2003 to go to court that I knew I was charged with killing migratory birds.”

He told the Nation that he also hunts in Notre Dame du Nord near the Ontario border and has never had a problem, despite the constant contact with the game wardens.

Cooper said that the only reason the Grand Council is even looking at the file is because he’s taken such a hard stance against pleading guilty that they are trying to save face.

“I told Ted Moses that I would never plead guilty and never stop fighting for my rights,” said Cooper, who admitted Moses never personally told him to plead guilty. “I guess when they realized I wouldn’t go away they decided to do something about it.”

After failing to find a defense lawyer to represent him because the costs would have bankrupted his cleaning company, Cooper was found guilty on November 8, 2004, the third time he was to appear in court. He was fined $611.

The court’s point of view, according to Cooper, was such that an agreement can be signed with a farmer, but only in the south. Further, they wanted him to prove his aboriginal ancestry in court. He said that he thought about doing that, even though he found it absurd, but it would have broken his company’s back.

“A lot of the younger generation is losing this way of life,” he said. “I hope I can influence them to get back into the traditional ways. I’m not trying to cause trouble, I’m just there to hunt; that’s what I do.

“After the incident, what bothered me the most was my son didn’t want to go hunting with me after that. He told me he was scared that those guys would come back, he was 15 at the time. Our culture is distinct because we live in both worlds; the society we’re in today and the Cree world.

“But if we let go of the Cree world, we’re lost in this society.”