My mother, Lucy Bosum, wept as she heard the decision of my grandparents. The answer was “No!” My biological father, Cyprien Caron, had proposed to marry my mother, but my grandparents could not overlook the clash of their cultures and languages. They could not conceive of this union being a possible match for my mother. My father, discouraged to learn of the decision, walked away from our little village never knowing what their futures would have in store. Sadly, shortly afterwards, and perhaps it was due to his troubled and distracting thoughts, he had an accident in the mine where he worked near Chibougamau. He was ambulanced to Quebec City.

My mother, Lucy Bosum, wept as she heard the decision of my grandparents. The answer was “No!” My biological father, Cyprien Caron, had proposed to marry my mother, but my grandparents could not overlook the clash of their cultures and languages. They could not conceive of this union being a possible match for my mother. My father, discouraged to learn of the decision, walked away from our little village never knowing what their futures would have in store. Sadly, shortly afterwards, and perhaps it was due to his troubled and distracting thoughts, he had an accident in the mine where he worked near Chibougamau. He was ambulanced to Quebec City.

This took place in the 1950s, when it was virtually impossible for my mother and father to communicate with one other. The village was really an informal settlement without a real address, so mail was not an option. To travel between Chibougamau and Quebec City was unthinkable in those days as the roads were very rudimentary, and gradually people in the village assumed that my father had passed away.

When a young woman bore a child in the traditional Cree culture, the Elders would arrange a marriage between couples. It was a lot about surviving and having the means to raise the child. It was much less, in past times, about romantic love. So it was that my mother met her husband, Sam Neeposh. This was the man who raised me until I was 14 years old, and I have always been grateful to him. But I grew up knowing he wasn’t my biological father.

Cyprien Caron returned to Chibougamau two years later and learned about the marriage. If his intention was to once again try with my grandparents to win my mother’s hand, his hopes were quickly dashed when he realized that it was too late. He had to accept the decision of the Elders and the reality of the marriage, and he had to move on eventually leaving the region with everyone believing that he would never be seen again. I grew up never knowing my biological father – until 53 years later.

Reminiscing over the years about my childhood, I recall the feelings many times of not having a biological father. My mother would talk about him in passing from time to time and I often wondered what he looked like. It was very hard for me to talk to my mother about my father. I was afraid to ask her questions probably, realizing in hindsight, because I was afraid of the answers I might get.

I would envy my friends when they talked about their special moments – even their ordinary moments – with their dads, listening to the fathers brag about their sons on killing their first goose, their first moose or the first bear or bragging about all kinds of accomplishments. You see, in the Cree culture you are marked as a good hunter by your ability to learn at a young age to bring home game to share with the family or with the larger community. I pretended that I didn’t care about these things, but deep down I wished I could have had just one such experience with my own father – just one of those special moments, someone to brag about an accomplishment of mine.

I know that my mother spoke to Sophie, my wife, about her relationship with my father. I am grateful for that. I suspect that they had their secret conversations.

I know that my mother spoke to Sophie, my wife, about her relationship with my father. I am grateful for that. I suspect that they had their secret conversations.

The search and eventual connection with my father is a script made for the movies. Many people helped shape this part of my personal story, all of whom I will be forever grateful to. One summer day in 2008, a new chapter in my life was being written. Sophie had been in Chibougamau earlier that day with one of my grandsons when a Cree Elder approached her and said he had just seen my father in the shopping mall. Sophie dropped what she was doing and ran to the mall, grandson in tow, to catch a glimpse of this man.

Unfortunately she did not find him but this was the spark for the search of a man I knew very little about. We started to ask people in the community about their recollections of my father, more specifically, if they remembered his name. Many told us it was an unusual name, a hard one to remember. I went back to Henry Salt, the Elder who initially spotted my father in the mall to see if he could help. Henry suggested I try to locate an elderly man in Chapais by the name of Mr. Caron who he thought might be related or might have known my father from the past.

I found Mr. Caron who I guessed to be in his 70s and I introduced myself. I asked him if he knew my biological father. He looked up at me and asked if I was an Indian. I replied, “Yes I am, my mother is Cree.” He quickly told me it was impossible, that we couldn’t be related. I couldn’t get myself to leave his doorstep. I had a feeling that this was the key I had been looking for. I continued to ask him questions about his family, names of his brothers who may have worked in the region in the 1950s. As he started naming them, one name stood out to me and I asked him to write it down for me. As I walked away with this name on a piece of paper, I had a feeling of hope. I immediately shared the name with Sophie and my daughter, Irene, still not quite clear on the first name as I could not make out Mr. Caron’s cursive writing. Irene quickly took to her computer that day and started an online search.

At 4 am the following day, my cell phone would not stop ringing. I finally answered it to hear my daughter’s excited voice on the line. I remember her telling me she found a man by the name of Cyprien Caron living in Oka, Quebec – 45 minutes from Montreal, the city I spent lots of time in for work. She proceeded to tell me she also found a photo, which she emailed me and asked that I take a look at it in the morning when I woke up. Needless to say, I could not sleep after that life-changing phone call. I began to feel emotional, frightened to be taking this next step as it was becoming all too real way too fast.

I decided to get up and I started to roam the Montreal hotel where I was staying, my mind racing. Excited and nervous, I decided to drive to the address that Irene had located not knowing what I was going to do when I got there. Disbelief set in as I drove to Oka, thinking that my father could be so close. I parked my vehicle nearby and decided, for lack of a more gentle word, to “stalk” Mr. Caron.

While waiting I decided to tell my children what I was doing. Despite their warnings of this possibly being illegal, I felt I had no other option. I was so close and I suddenly felt a longing to see him in person.

After 53 years, although from a distance and only for a brief moment, I finally saw him for the first time as he stepped out of his home with his wife.

Later that week, I approached Mabel Herodier of the Cree Board of Health and Social Services and asked for her advice. She suggested I speak to Marcel Villeneuve, a consultant to the Health Board, who suggested I engage a communications specialist for these types of family situations. Marie Dequier of Granby, Quebec, agreed to take on my case. So the process began of finding a way to communicate with Mr. Caron. It took about three weeks. Throughout this time, and even though my family initially tried to dissuade me from the idea, my whole family got involved taking turns stalking Mr. Caron and his family.

After many attempts, it was on August 9, 2008, that Mrs. Dequier reported to me that she spoke to Mr. Caron, who confirmed knowing my mother Lucy and was ready to meet me. The magnitude of this revelation was both momentous and overwhelming.

Then came the days leading up to the eventual meeting with my father. These were very unsettling moments that made me feel like a young boy again. I was experiencing strange feelings that I had never had before, and I was in turmoil. I did not know how to react, I did not know what I would say and I certainly did not know what I would do when I met him. I was nervous, afraid of the unknown, I could not relax and I could not sleep. I could not stop thinking about him and what our encounter would be like. I had a lot of questions, everything from wondering where he lived, what he did in life, was he healthy, did he have a family and do I have siblings?

On a deeper emotional level there were questions like: Did he love me? Why didn’t he try to connect with me? Will he accept me or reject me!

The day we finally met was at his home in St-Joseph-du-Lac, on August 19, 2008, at 3 pm. I was very nervous and excited all at the same time. It was like being in a dream. During my career, I have met prime ministers, premiers, Nobel laureates and international dignitaries. Yet this was to be the most important meeting of my life. Do I shake his hand or do I hug him? As I approached him, he reached out to me, hugged me and whispered, “My son, I am so happy, I love you!”

When we got through the introductions and we were in the kitchen we were like kids, sharing stories of our past, joking, laughing as if we had known each other for a long time, hugging and smiling at each other. That was an evening I will cherish for the rest of my life!

I shared with him stories of my life growing up and the wonderful family I was blessed with. Sophie and I showed pictures of our children and grandchildren. I explained the different occupations we held in our communities. I explained my role with the Cree Nation and with Aboriginal issues in general.

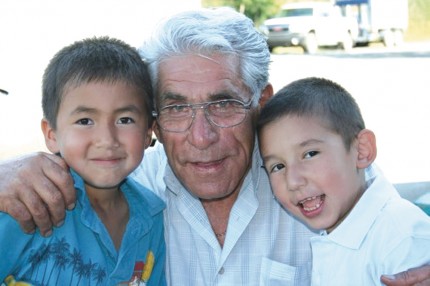

Family Reunion: Reggie Bosum, Irene B. Quinn, Cyprien & Rejeanne Caron, Sophie H. Bosum, Abel Bosum, Curtis Bosum, Nathaniel Bosum

Thinking back on the time I had with my dad, I can now say that many of the longings I had as a child were finally fulfilled. We went fishing on Lake Mistissini; we went deer hunting at his camp; we watched my son, Nathaniel, race at the Montreal Olympic Stadium; he visited my family in Oujé-Bougoumou, Mistissini and Waswanipi. We spent birthdays and other family celebrations together. We held hands and we hugged each other every time we met.

As the years passed I could see that we had similar interests in life. I realized that I was like my dad in many ways. Of course, Sophie would attribute my stubborn character to him as well as my love for the environment. Others saw similarities in our facial features and posture. There were comparisons with our work and various achievements in life. Some said they saw similarities in generosity and compassion for others.

Most importantly, we forgave each other. We forgave each other for the 53 years of missed connection and missed opportunities. In our own way, we made our “peace agreement.” I understood how hard it must have been for him to keep a secret from his family and friends for so many years and I knew that he was finally at peace with himself when he could reveal that part of his past and release the associated emotions after holding them in for so long. And I think he understood how hard it was for me growing up without a father. Cyprien became a really good friend and I respected him. I had a father, a real dad.

I was deeply saddened when I heard the news that my dad was hospitalized with pneumonia. I once again had very mixed emotions. I had compassion for him not wanting him to be ill and not wanting him to suffer. At the same time, there was anger in my heart. My dad was possibly going to leave me again and I would once more be deprived of a father. I had taken a risk to open myself emotionally and now the consequence would be another loss. But after discussing my feelings with Sophie and with my children, in the end I found peace in my heart realizing that I was, in reality, very fortunate. I was one of the very few people who ever got a second chance to meet the father they always longed for.

As I sat in his hospital room, I watched the clock tick away. Our moments together were ticking away too. I would lean over and listen to his heart tick away and for my own selfish reasons I prayed that it would not stop ticking. I believe my prayers were answered with the extra days I spent with him. I spent most of my time with him in those final days trying to remember how we spent our time together over the previous six years and questioning myself about whether I did enough to express my feelings towards him.

Over the course of the brief years we had together, he answered the most important question I had for him. Yes, he loved me unconditionally. And he also loved my family and he showed it at every possible opportunity toward my children and grandchildren. My family is very happy and fortunate to have had the privilege of knowing him, to spend some of these six years together, to enjoy life together and, of course, to get to know each other as family. Just as it was important for me to know who my father was, it was also important for my family to know who their father-in-law, grandfather, and great-grandfather was. Realizing that brought us all closer.

This was all I every really wanted, for him to fill the void in my life.

Cyprien touched my life profoundly and that of my family. Yes, I am grieving now, but it is because we had the courage to find each other and love each other. Grieving only happens where there has been love. That is the way life is.

“Cyprien, it broke my heart to lose you but you did not go alone, a part of me went with you the day God took you home. In life I love you dad and in death I love you still, in my heart you will hold a place no one could ever fill!”

By finding my dad, Cyprien, I found myself.